For months, the coronavirus has exacerbated global tensions, but it’s been a particularly rough week for China with diplomatic stoushes exploding on multiple fronts.

Beijing’s move to politically clamp Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement with a sweeping new national security law has sparked a backlash in Western countries that’s now seeing extradition treaties suspended, including in Australia.

The long-running trade and technology war with the United States has also moved up a gear with the Trump administration finally finding a way to force the UK away from using Huawei in its 5G roll out.

And making matters worse for Beijing, India is now waging its own technology battle against Chinese companies in an unexpected broadside.

But Hong Kong still remains the biggest flashpoint, with Scott Morrison yesterday announcing he would suspend an extradition treaty with Hong Kong and provide a visa pathway for Hong Kongers already eligible to temporarily live in Australia as well as businesses.

It received a mixed reaction in Hong Kong among pro-democracy figures — many had hoped for a special intake offer for Hong Kongers.

In the words of one lawyer who spoke to the ABC, the move was as “loud thunder but only tiny drops of rain” — a Chinese idiom.

But prominent Hong Kong pro democracy activist Joshua Wong said: “Australia’s new visa policy serves as an essential safe haven for freedom-loving Hong Kongers that flee political persecution under China’s new Orwellian law”.

China’s view is that Australia is a pawn of the US

In response to yesterday’s announcement, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman, Zhao Lijian, said Australia’s decisions were “grave violations of international law and basic norms of international relations” and that China reserved the right to “take actions” against the Australian side.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China said they expressed “deep regret and disappointment over Australia’s decision to suspend the agreement on surrender of fugitive offenders, which allows political agenda to override legal cooperation in criminal matters”.

From China’s perspective, Australia’s moves are completely political, according to analysts in Beijing.

They have privately expressed bewilderment with the Australian Government’s increasingly firm stance towards China.

Earlier this week, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) also warned Australians in Hong Kong could be at “increased risk of detention on vaguely defined national security grounds”.

It came just two days after DFAT updated travel advice for Australians in mainland China, saying they could be at risk of “arbitrary detention”.

Close observers of the relationship — few of whom want to publicly speak on the record to Australian media — have largely dismissed Australia’s motivations for this decision.

The tensions have built for years but accelerated when China took offence at Australia’s call for an independent probe on the coronavirus.

An update on that mission came this week with a team of investigators from the World Health Organization (WHO), set to arrive in China to begin their study. But the specifics of the mission remain under a shroud of mystery.

Beijing, seemingly in response to Australia’s original call for an investigation, curtailed some beef exports for labelling violations and slapped a tariff on the country’s barley two months ago.

Since then, we’ve seen Beijing warn students to avoid coming to Australia citing an increase in racist attacks.

China’s Government views Australia not as an independent player, but largely as a pawn of the US — where tensions ramped up even further this week.

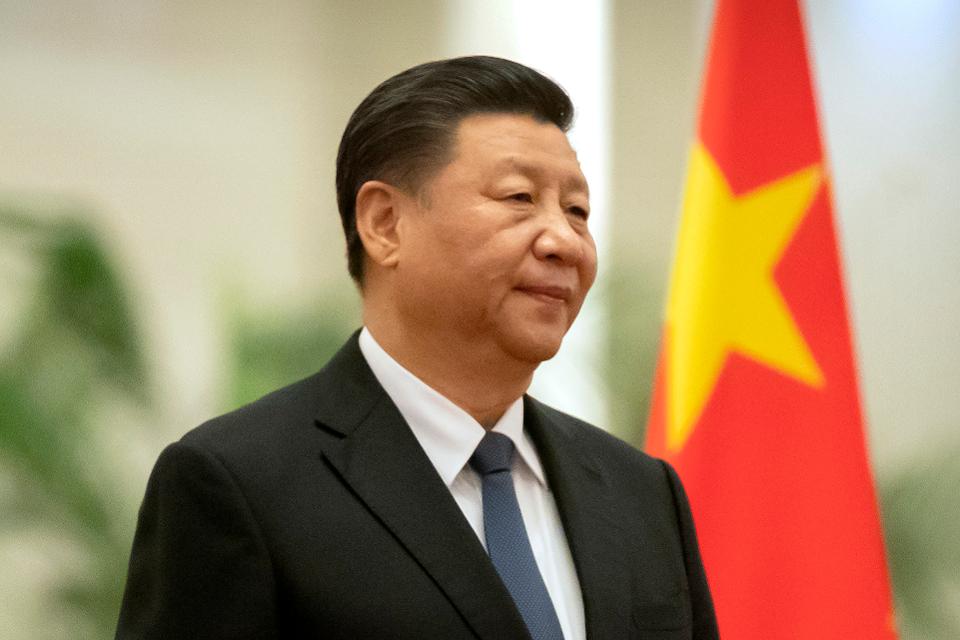

The head of the FBI suggested Chinese officials had been trying to force people to return to China from the US under a program of coercion led by President Xi Jinping.

But none of this is particularly new to China’s Government.

“Due to ideological bias, some Americans are sparing no effort to view China as an adversary or even an enemy, trying every means to contain China’s development and obstruct China-US relations,” Foreign Minister Wang Yi said.

India makes a move out of China’s playbook

Chinese tech companies have also faced their own reckoning this week.

Having explosively grown over the past 10 years after China’s Government blocked their much more established American rivals from the local market, they’re now experiencing a taste of what that must have felt like.

But the karma comes not from the US — well not yet anyway — but from an even bigger market.

India’s Government sensationally announced two weeks ago it would ban 59 apps — all of them Chinese — on national security grounds.

Over the past week, it’s become clear India isn’t bluffing, with the biggest Chinese app by users there — TikTok — voluntarily withdrawing its services in India to comply. It hopes to appeal.

The timing of the announcement came just days after Chinese troops killed 20 Indian soldiers along their hotly disputed border high in the Himalayas.

The Chinese military won’t reveal how many Chinese soldiers died, so the nationalist anger has burned a lot more deeply in India.

While the ban is primarily based on concerns Indian user data will end up in China, Delhi may be playing the long game based on China’s textbook.

In 2007 to 2008, sites like YouTube and Facebook were accessible in China.

By 2010, the Communist Party decided they posed too much political risk to its iron grip on information.

These days, most of the services that the rest of the world rely on — Google, WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter — are missing from China’s internet.

But the censorship had a second and potentially more important purpose.

A whole host of domestic apps blossomed without American competition in China’s massive market and have now grown to be global behemoths, with WeChat and TikTok leading the way.

With India’s burgeoning tech scene yet to develop any major apps, these Chinese companies have been expanding rapidly in a bid to take on the American rivals in India — particularly TikTok.

The ban not only hurts the aspirations of these Chinese companies to expand abroad, but could provide a bit more space for India’s domestic tech industry to develop its own apps and services.

US signals ban after tech companies turn sour on China

And then there’s the US.

If Chinese tech companies weren’t rattled by the India ban, they would have been by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo saying the US was “looking at” banning Chinese apps too.

He was light on detail and legal experts questioned how easy it would be for the Trump administration to do it, but it appeared India served as the inspiration.

With few exceptions, US tech companies have dramatically soured on China in recent years with Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg leading the way.

His ingratiation efforts to get Facebook unbanned from the Chinese market in some form were infamous.

Reportedly asking Chinese Communist Party chief Xi Jinping to name his unborn child, jogging around Tiananmen Square, reading Mr Xi’s book and even learning Mandarin.

Like Rupert Murdoch many years before him, Mr Zuckerberg learnt the hard way that money, flattery and power don’t open doors in China like they do in the West.

Having failed, he’s now seeing Chinese tech companies as posing risks, not just to his companies but the internet as we know it.

“While our services like WhatsApp are used by protesters and activists everywhere due to strong encryption and privacy protections, on TikTok — the Chinese app — mentions of these same protests are censored, even here in the US,” he told an audience at Georgetown University last year.

“Is that the internet we want?”

Google too has made creative but ultimately futile efforts to get back into China — including a man-versus-AI game of Go, a popular strategy boardgame in China.

So where does this leave Beijing?

China’s Government has long prepared for pushback from the US, but the increasingly fraught India relationship chips away at Beijing’s hopes to largely cultivate good relations with non-Western countries.

The tech troubles are far from clear. But China’s Government appears to be resigned to permanently worsening ties with Washington, although some analysts believe a Biden administration would ease off the confrontational path.

Australia’s relationship with China is seen in Beijing in much the same light, with no warming expected anytime soon.

Even if nothing changes, “the possibility of a comprehensive confrontation is low”, China Foreign Affairs University analyst Su Hao was quoted in the Global Times as saying.

Source: ABC NEWS & Writer- Bill Birtles

WhatsApp us

WhatsApp us